Week 2 [Mon, Jan 19th] - Topics

Detailed Table of Contents

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Given this is a first course in SE, tradition demands that we start by defining the subject. However, let's not spend a lot of time going through lengthy/formal definitions of SE. Instead, let's look at an extract from the very first chapter of a very famous SE book, with the aim of providing some inspiration, but also an appreciation of the challenges ahead.

The following description of the Joys of the Programming Craft was taken (and emphasis added) from Chapter 1 of the famous book The Mythical Man-Month, by Frederick P. Brooks.

Why is programming fun? What delights may its practitioner expect as his reward?

First is the sheer joy of making things. As the child delights in his mud pie, so the adult enjoys building things, especially things of his own design. I think this delight must be an image of God's delight in making things, a delight shown in the distinctness and newness of each leaf and each snowflake.

Second is the pleasure of making things that are useful to other people. Deep within, you want others to use your work and to find it helpful. In this respect the programming system is not essentially different from the child's first clay pencil holder "for Daddy's office."

Third is the fascination of fashioning complex puzzle-like objects of interlocking moving parts and watching them work in subtle cycles, playing out the consequences of principles built in from the beginning. The programmed computer has all the fascination of the pinball machine or the jukebox mechanism, carried to the ultimate.

Fourth is the joy of always learning, which springs from the nonrepeating nature of the task. In one way or another the problem is ever new, and its solver learns something: sometimes practical, sometimes theoretical, and sometimes both.

Finally, there is the delight of working in such a tractable medium. The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought-stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by the exertion of the imagination. Few media of creation are so flexible, so easy to polish and rework, so readily capable of realizing grand conceptual structures....

Yet the program construct, unlike the poet's words, is real in the sense that it moves and works, producing visible outputs separate from the construct itself. It prints results, draws pictures, produces sounds, moves arms. The magic of myth and legend has come true in our time. One types the correct incantation on a keyboard, and a display screen comes to life, showing things that never were nor could be.

Programming then is fun because it gratifies creative longings built deep within us and delights sensibilities you have in common with all men.

Not all is delight, however, and knowing the inherent woes makes it easier to bear them when they appear.

First, one must perform perfectly. The computer resembles the magic of legend in this respect, too. If one character, one pause, of the incantation is not strictly in proper form, the magic doesn't work. Human beings are not accustomed to being perfect, and few areas of human activity demand it. Adjusting to the requirement for perfection is, I think, the most difficult part of learning to program.

Next, other people set one's objectives, provide one's resources, and furnish one's information. One rarely controls the circumstances of his work, or even its goal. In management terms, one's authority is not sufficient for his responsibility. It seems that in all fields, however, the jobs where things get done never have formal authority commensurate with responsibility. In practice, actual (as opposed to formal) authority is acquired from the very momentum of accomplishment.

The dependence upon others has a particular case that is especially painful for the system programmer. He depends upon other people's programs. These are often maldesigned, poorly implemented, incompletely delivered (no source code or test cases), and poorly documented. So he must spend hours studying and fixing things that in an ideal world would be complete, available, and usable.

The next woe is that designing grand concepts is fun; finding nitty little bugs is just work. With any creative activity come dreary hours of tedious, painstaking labor, and programming is no exception.

Next, one finds that debugging has a linear convergence, or worse, where one somehow expects a quadratic sort of approach to the end. So testing drags on and on, the last difficult bugs taking more time to find than the first.

The last woe, and sometimes the last straw, is that the product over which one has labored so long appears to be obsolete upon (or before) completion. Already colleagues and competitors are in hot pursuit of new and better ideas. Already the displacement of one's thought-child is not only conceived, but scheduled.

This always seems worse than it really is. The new and better product is generally not available when one completes his own; it is only talked about. It, too, will require months of development. The real tiger is never a match for the paper one, unless actual use is wanted. Then the virtues of reality have a satisfaction all their own.

Of course the technological base on which one builds is always advancing. As soon as one freezes a design, it becomes obsolete in terms of its concepts. But implementation of real products demands phasing and quantizing. The obsolescence of an implementation must be measured against other existing implementations, not against unrealized concepts. The challenge and the mission are to find real solutions to real problems on actual schedules with available resources.

This then is programming, both a tar pit in which many efforts have floundered and a creative activity with joys and woes all its own. For many, the joys far outweigh the woes....

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Now, let's switch our focus to the project management aspect of SE.

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to doing a software project. Those two approaches are also highly relevant to the way this course is run, and how it is different from most SE courses elsewhere.

Let's learn about those two approaches early so that we can better understand how this course works.

Software development goes through different stages such as requirements, analysis, design, implementation and testing. These stages are collectively known as the software development lifecycle (SDLC). There are several approaches, known as software development lifecycle models (also called software process models), that describe different ways to go through the SDLC. Each process model prescribes a 'roadmap' for the software developers to manage the development effort. The roadmap describes the aims of the development stages, the outcome of each stage, and the workflow i.e., the relationship between stages.

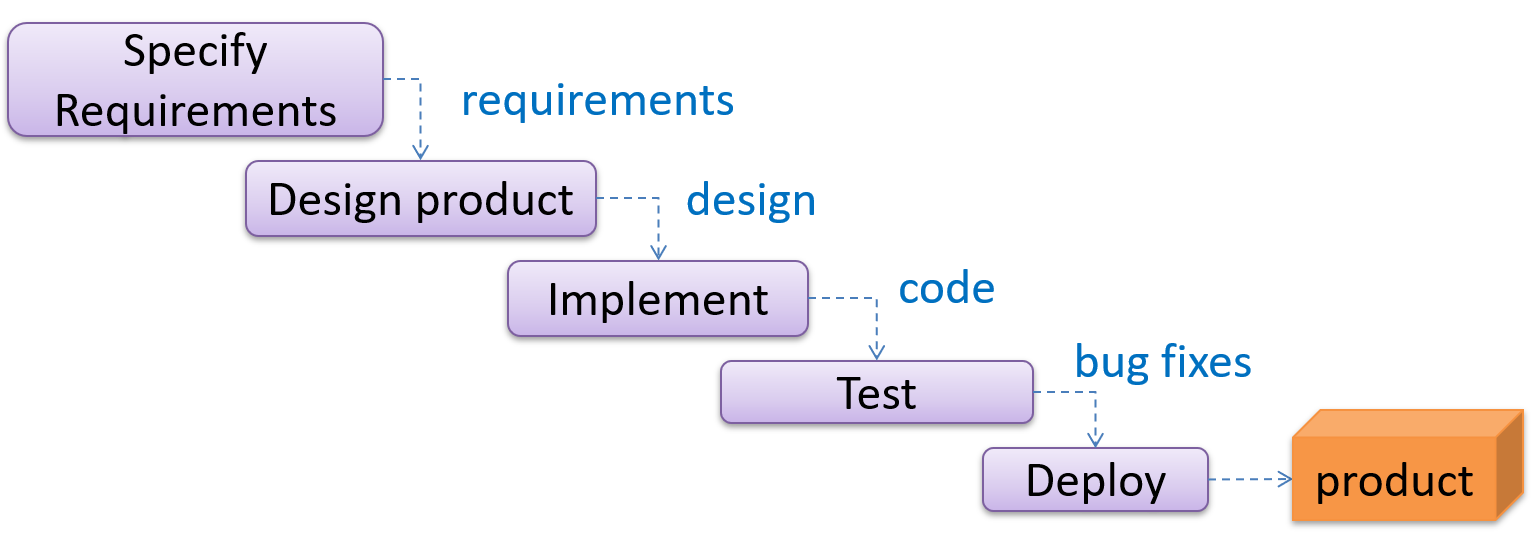

The sequential model, also called the waterfall model, views software development as a linear process, in which the project is seen as progressing through the development stages. The name waterfall stems from how the model is drawn to look like a waterfall (see below).

When one stage of the process is completed, it produces some artifacts to be used in the next stage. For example, the requirements stage produces a comprehensive list of requirements, to be used in the design phase.

A strict sequential model project moves only in the forward direction i.e., each stage is completed before starting the next. For example, once the requirements stage is over, there is no provision for revising the requirements later.

This model can work well for a project that produces software to solve a well-understood problem, in which case the requirements can remain stable and the effort can be estimated accurately. Furthermore, as each stage has a well-defined outcome, it is easy to track the progress of the project because one can gauge the project progress by monitoring which stage the project is in.

However, real-world projects often tackle problems that are not well-understood at the beginning, making them unsuitable for this model. For example, target users of a software product may not be able to state their requirements accurately at the start of the project, if they have not used a similar product before.

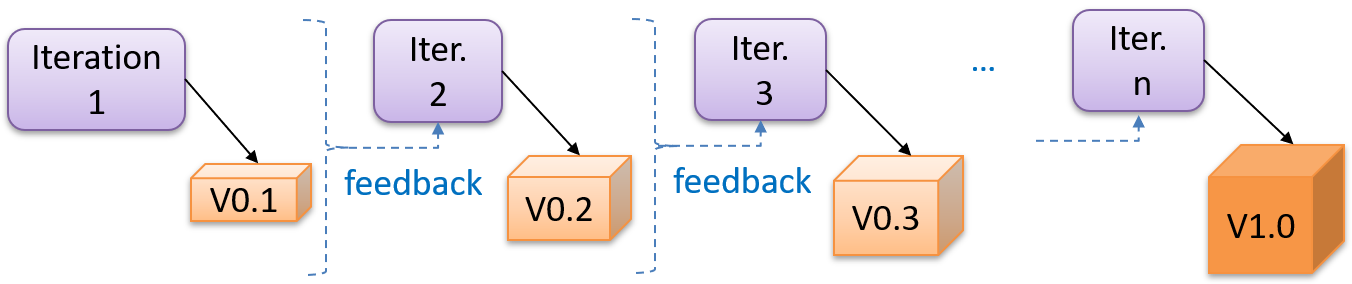

The iterative model advocates producing the software by going through several iterations. Each of the iterations could potentially go through all the stages of the SDLC, from requirements gathering to deployment.

Each iteration produces a new version of the product, building upon the version produced in the previous iteration. Feedback from each iteration is factored into the subsequent iterations. For example, if an implementation task took longer than expected, the effort estimate for a similar tasks in future iterations can be adjusted accordingly. Similarly, if a feature introduced in the current iteration was not well-received by target users, it can be removed or tweaked in the next iteration.

The iterative model can be done in breadth-first or depth-first approach.

- In the breadth-first approach, an iteration evolves all major components and all functionality areas in parallel i.e., most features and most will be updated in each iteration, producing a working product at the end of each iteration.

- In the depth-first approach, an iteration focuses on fleshing out only some components or some functionality area. Accordingly, early depth-first iterations might not produce a working product.

Taking a Minesweeper game as an example,

- breadth-first iterations will deliver a fully playable version early. These early versions may have primitive functionality, for example, a rudimentary text based UI, fixed board size, limited minefield layouts, etc. These functionalities (and corresponding components) will then be improved in later releases.

- an early depth-first iteration could deliver the full user interface (UI) but with no game logic at all. Alternatively, an early iteration could focus on just the logic for generating initial layouts of the minefield. Neither will be a playable version of the game but both can be used to collect early feedback (about the UI, and the initial minefield layouts, respectively) which can then be used to guide later iterations.

A project can be done as a mixture of breadth-first and depth-first iterations i.e., an iteration can contain some breadth-first work as well as some depth-first work, or, some iterations can be breadth-first while others are depth-first.

Follow up notes for the item(s) above:

Scanning a TLDR version of a topic: As mentioned in 'Using this Website' page, the more important layer of information is given in bold text. For example, you can quickly scan the essential points of a topic by reading the bold text only (this could be useful when you want to quickly recap a previous topic, or to get an idea of what a topic covers without reading all the details).

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Next, let's resume our Git Learning Trial, covering a few more tours. the first two focus on working with GitHub, while the other two focus on getting more out of the Git revision history.

See Git-Mastery → Tour 2: Backing up a Repo on the Cloud

See Git-Mastery → Tour 3: Working Off a Remote Repo

See Git-Mastery → Tour 4: Using the Revision History of a Repo

See Git-Mastery → Tour 5: Fine-Tuning the Revision History

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you are likely to be using an IDE for the iP, let's learn at least enough about IDEs to get you started using one.

🤔 In case you are puzzled by the sudden change of topic, it's because we take an iterative approach to covering topics, as explained in the panel below:

Professional software engineers often write code using Integrated Development Environments (IDEs). IDEs support most development-related work within the same tool (hence, the term integrated).

An IDE generally consists of:

- A source code editor that includes features such as syntax coloring, auto-completion, easy code navigation, error highlighting, and code-snippet generation.

- A compiler and/or an interpreter (together with other build automation support) that facilitates the compilation/linking/running/deployment of a program.

- A debugger that allows the developer to execute the program one step at a time to observe the run-time behavior in order to locate bugs.

- Other tools that aid various aspects of coding e.g., support for automated testing, drag-and-drop construction of UI components, version management support, simulation of the target runtime platform, modeling support, AI-assisted coding help, collaborative coding with others.

Examples of popular IDEs:

- Java: Eclipse, IntelliJ IDEA, NetBeans

- C#, C++: Visual Studio

- Swift: XCode

- Python: PyCharm

- Multiple languages: VS Code

Some web-based IDEs have appeared in recent times too e.g., Amazon's Cloud9 IDE.

Some experienced developers, in particular those with a UNIX background, prefer lightweight yet powerful text editors with scripting capabilities (e.g., Emacs) over heavier IDEs.

Refer to these se-edu guides:

- Intellij IDEA: Setting up

- VS Code: Refer to the first few tutorials given here.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you start adding features to your project iteratively, you'll need a way to detect if the new code breaks the existing code. Next, let's learn a rather simple way to do that using a certain type of testing (we'll be learning more sophisticated methods in later weeks).

This also means we are now switching focus from the implementation aspect to the testing aspect of SE.

Testing: Operating a system or component under specified conditions, observing or recording the results, and making an evaluation of some aspect of the system or component. –- source: IEEE

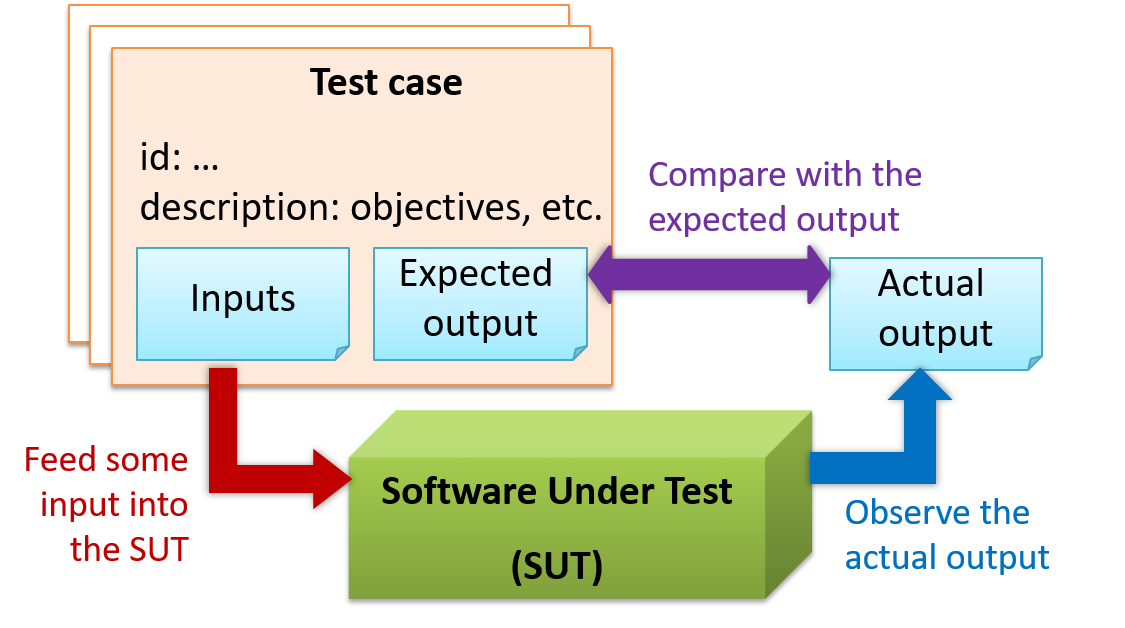

When testing, you execute a set of test cases. A test case specifies how to perform a test. At a minimum, it specifies the input to the software under test (SUT) and the expected behavior.

Example: A minimal test case for testing a browser:

- Input – Start the browser using a blank page (vertical scrollbar disabled). Then, load

longfile.htmllocated in thetest datafolder. - Expected behavior – The scrollbar should be automatically enabled upon loading

longfile.html.

Test cases can be determined based on the specification, reviewing similar existing systems, or comparing to the past behavior of the SUT.

For each test case you should do the following:

- Feed the input to the SUT

- Observe the actual output

- Compare actual output with the expected output

A test case failure is a mismatch between the expected behavior and the actual behavior. A failure indicates a potential defect (or a bug) -- we say 'potential' because the error could be in the test case itself.

Example: In the browser example above, a test case failure is implied if the scrollbar remains disabled after loading longfile.html. The defect/bug causing that failure could be an uninitialized variable.

When you modify a system, the modification may result in some unintended and undesirable effects on the system. Such an effect is called a regression.

Regression testing is the re-testing of the software to detect regressions. The typical way to detect regressions is retesting all related components, even if they had been tested before.

Regression testing is more effective when it is done frequently, after each small change. However, doing so can be prohibitively expensive if testing is done manually. Hence, regression testing is more practical when it is automated.

An automated test case can be run programmatically and the result of the test case (pass or fail) is determined programmatically. Compared to manual testing, automated testing reduces the effort required to run tests repeatedly and increases precision of testing (because manual testing is susceptible to human errors).

Resources:

- [Quora post] What is the best way to avoid bugs

- [Quora post] Is automated testing relevant to startups?

A simple way to semi-automate testing of a CLI (Command Line Interface) app is by using input/output re-direction. Here are the high-level steps:

- First, you feed the app with a sequence of test inputs that is stored in a file while redirecting the output to another file.

- Next, you compare the actual output file with another file containing the expected output.

Let's assume you are testing a CLI app called AddressBook. Here are the detailed steps:

Store the test input in the text file

input.txt.Example

input.txtStore the output you expect from the SUT in another text file

expected.txt.Example

expected.txtRun the program as given below, which will redirect the text in

input.txtas the input toAddressBookand similarly, will redirect the output ofAddressBookto a text fileoutput.txt. Note that this does not require any changes inAddressBookcode.java AddressBook < input.txt > output.txtThe way to run a CLI program differs based on the language.

e.g., In Python, assuming the code is inAddressBook.pyfile, use the command

python AddressBook.py < input.txt > output.txtIf you are using Windows, use a normal MS-DOS terminal (i.e.,

cmd.exe) to run the app, not a PowerShell window.

Next, you compare

output.txtwith theexpected.txt. This can be done using a utility such as Windows'FC(i.e., File Compare) command, Unix'sdiffcommand, or a GUI tool such as WinMerge.FC output.txt expected.txt

Note that the above technique is only suitable when testing CLI apps, and only if the exact output can be predetermined. If the output varies from one run to the other (e.g., it contains a time stamp), this technique will not work. In those cases, you need more sophisticated ways of automating tests.

Follow up notes for the item(s) above:

Congrats! You've made it to the end of this week's topics. It feels like a lot right now but now that we got an early start, this stuff will be second nature to you by the time you are done with the semester. 😃